Toshihiro Menju, Atsuko Geiger

September 2012

PDF download

In the immediate aftermath of the massive earthquake and tsunami that hit northeastern Japan on March 11, 2011, people around the world began mobilizing support for Japan. In the United States, not only did the government provide official assistance, but so far the American people have donated over $665 million to support the victims in Tohoku. This makes the Japan response the largest outpouring of US philanthropy in history for a disaster in another developed country.

One of the major reasons that the outpouring was so immense was the existence of strong grassroots ties between the peoples of the two countries. A clear example of this was the outpouring of support from US sister cities for their Japanese counterparts, demonstrating the importance of bonds that are nurtured through traditional exchange organizations that focus on building personal ties and friendships.

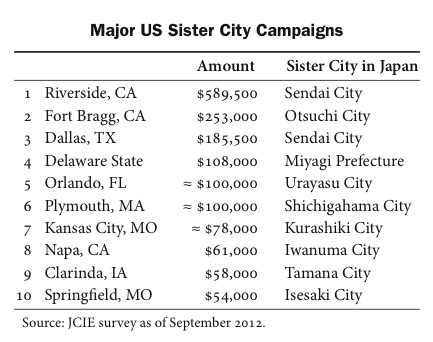

According to a JCIE survey, as of July 2012, at least 95 US towns, cities, and states that have sister cities in Japan had organized fundraising campaigns. In total, they raised more than $2.4 million for earthquake relief. Most of these funds were sent to the Japanese sister city for its own recovery or to be forwarded on to communities in the disaster zone or aid organizations that had been recommended by the sister city.

In Riverside, California, for example, residents raised $589,000 from more than 4,000 donors to help people in Sendai, the town’s sister city since 1957. Fort Bragg, California, a small beach town with a population of 7,000, raised more than $250,000 for its sister city, Otsuchi, located in Iwate Prefecture. Sister city associations in scores of other towns and cities across the country also raised funds for Japan, ranging from a few hundred to hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In Riverside, California, for example, residents raised $589,000 from more than 4,000 donors to help people in Sendai, the town’s sister city since 1957. Fort Bragg, California, a small beach town with a population of 7,000, raised more than $250,000 for its sister city, Otsuchi, located in Iwate Prefecture. Sister city associations in scores of other towns and cities across the country also raised funds for Japan, ranging from a few hundred to hundreds of thousands of dollars.

However, what has been most striking about the mobilization of support in the sister cities is not the amount of funds raised, but the fact that residents of these towns have been so heavily involved in the campaigns at a very personal level. From local government officials to elementary school children, individual residents took part in campaigns and donated funds out of a sincere desire to help their friends in Japan.

Fort Bragg and Otsuchi

The case of Fort Bragg is a particularly striking example. Forth Bragg and Otsuchi are coastal towns that are located directly across the Pacific Ocean on the same latitude. They officially became sister cities in 2005, and since then, the two towns have run exchange programs so that middle and high school students can stay with local families and take part in cultural activities in each other’s town.

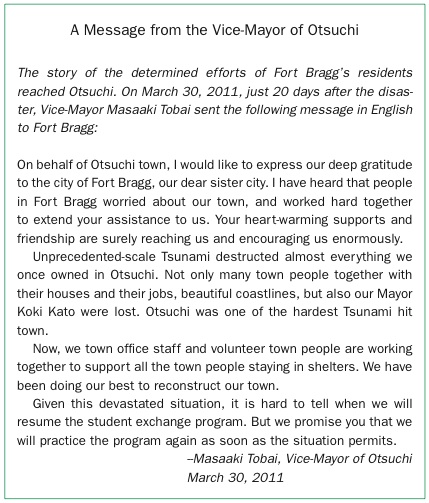

When the disaster struck, Otsuchi was one of the hardest hit towns. Its town hall was completely destroyed, the mayor was killed in the tsunami, and the fate of a quarter of the town employees was initially unknown. In the first few hours after the disaster, media reports of the devastation in Otsuchi reached the people of Fort Bragg. Members of the Fort Bragg–Otsuchi Cultural Exchange Association, a volunteer group that has been a central player in the sister city exchange programs, immediately set out to mobilize support for Otsuchi. On March 16, just five days after the disaster, the association established the Otsuchi Recovery Fund, utilizing its tax-exempt status. The following day, more than 30 Fort Bragg residents sat down to discuss how they could raise funds and how those funds should be used. Many agreed with the opinion that “Our funds should go directly to Otsuchi, instead of donating to the Red Cross.” Others noted, “Since we can’t send food and water from the United States, we should focus on recovery and reconstruction instead of immediate relief.” The residents exchanged various opinions and ideas, exploring the best way to help Otsuchi.

How were they able to raise such a large amount of funds in such a small town? Many different ideas were attempted in order to disseminate information about the fund as widely as possible. A Facebook page for the Otsuchi Recovery Fund was set up, and it was announced that the funds would directly go to the town of Otsuchi. Members of the local chamber of commerce collected contributions from local business owners. The mayor of Fort Bragg also made an appeal for support on a local radio program, while volunteers uploaded information and updates on the situation in Otsuchi on Wikipedia.

But Fort Bragg’s efforts to support Otsuchi went even further. They organized a fundraising event at an art gallery in town, where pictures and souvenirs from residents’ past trips to Otsuchi were displayed. They also created “Save Otsuchi” posters and “Support Otsuchi” T-shirts that were sold to raise funds. Local stores posted announcements of the recovery fund, and donation boxes were set up at restaurants, stores, and the farmers’ market.

And it did not stop there. Profits from the sale of music CDs from a local concert were donated; residents donated items to be sold at a fundraising garage sale; a local business made special bookmarks to be sold at a local bookstore so that the proceeds could go to the fund. For a small town, the range of ideas and efforts was truly impressive.

In addition to the fundraising efforts, people in Fort Bragg discussed the possibility of hosting residents and students from Otsuchi and began making arrangements with local families and schools. In short, they thought of every possible way that they could help their sister city.

Impact of Grassroots Ties

The case of Fort Bragg was extraordinary, but it was not unique. Many other cities in the United States that have sister cities in Japan launched similar efforts when they heard that their friends in Japan were in trouble. Countless benefits, charity garage sales, art auctions, and music concerts were organized to raise funds for Japan, and many volunteers donated their time and energy.

The residents of Fort Bragg and other US sister cities teach an important lesson about grassroots exchange. In recent years, some stakeholders of sister city programs have begun discussing the need to shift the purpose of exchanges from building friendship to focusing more on utilitarian goals. However, the stories of Fort Bragg and other sister cities remind us that the very foundation of international exchange is people-to-people interaction. The emotional bonds between people that emerge out of traditional grassroots exchange are resilient and have not become obsolete. Personal bonds like those between the residents of Fort Bragg and Otsuchi are nurtured through traditional cultural exchange programs between sister cities, like homestays and student exchanges.

The case of Fort Bragg and Otsuchi also demonstrated the utility of information technology. Blogs and Facebook became essential platforms for mobilizing support and facilitating communications. Even when there was limited access to electricity and landline phones in the disaster zone, Otsuchi residents in evacuation shelters could send e-mails to Fort Bragg from their cell phones to notify people that they were safe and update them on the conditions in Otsuchi. The information from Otsuchi was then uploaded on a blog by Fort Bragg volunteers to share with other residents. People in Otsuchi also began uploading their pictures and posting their comments directly on those Internet-based platforms, giving people in Fort Bragg real-time updates on what was going on in the disaster-hit areas.

The case of Fort Bragg and Otsuchi also demonstrated the utility of information technology. Blogs and Facebook became essential platforms for mobilizing support and facilitating communications. Even when there was limited access to electricity and landline phones in the disaster zone, Otsuchi residents in evacuation shelters could send e-mails to Fort Bragg from their cell phones to notify people that they were safe and update them on the conditions in Otsuchi. The information from Otsuchi was then uploaded on a blog by Fort Bragg volunteers to share with other residents. People in Otsuchi also began uploading their pictures and posting their comments directly on those Internet-based platforms, giving people in Fort Bragg real-time updates on what was going on in the disaster-hit areas.

Otsuchi Vice-Mayor Tobai noted that the support from across the ocean deeply touched the hearts of many Japanese people affected by the disaster. In turn, the words of sincere gratitude from Japanese friends encouraged those in the United States. In many ways, the March 11 disaster manifested the power of the “international social capital” that sister cities have developed over the years.

In the coming years, as the local communities in the disaster-hit areas in Tohoku must focus on the challenge of recovery and reconstruction, they will have limited financial and human resources to continue their international exchange programs. In some cases, the fear of radiation and other new factors will make it difficult for sister cities to sustain exchange programs as they have in the past. However, creative efforts have been made to maintain the connection in new ways. In Dallas/Fort Worth, for example, a local radio station produced a special program in which letters were presented from ordinary people in its sister city of Sendai who wished to thank the people of Dallas/Fort Worth for their support. They shared deeply personal accounts of their lives, challenges, and dreams in the aftermath of the disaster. In return, listeners in Texas posted their messages to the people in Sendai on the radio station’s website.

The remarkable contributions of US sister city associations underscore just how crucial the bonds of international friendship can be in a time of need. As communities in Tohoku recover, it seems clear that they will continue to find grassroots ties to their counterparts in the United States and the rest of the world an important asset.

This report was prepared by Atsuko Geiger and Toshihiro Menju based on Menju’s article originally published in Nippon NPO Gakkai (Japan NPO Research Association) no. 48 (June 2011). We are grateful to numerous groups and individuals, especially the Japan Local Government Center (CLAIR, New York), for providing valuable data on fundraising campaigns.