July 2014

PDF Download

An earlier version of this working paper was published in Rebuilding Sustainable Communities after Disasters in China, Japan and Beyond, edited by Adenrele Awotona (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014).

I was still fumbling with the lock on the office door when the phone started ringing. It was already late but I had spent the first two hours that morning calling around Tokyo to make sure that my brother and my colleagues were safe after the day’s massive earthquake. When I finally made it inside and picked up the phone, a Congresswoman was on the line to ask for the latest report from Japan and to express her sympathy for the victims of the unfolding tragedy. She was clearly shaken and struggled to maintain her composure. As soon as I put the receiver back in the cradle, it rang again. This time it was a schoolteacher who saw that our organization’s name began with “Japan” and wanted advice on things that her students could do to support relief efforts. By the time that call ended, several of our other lines were lighting up. The ringing was to continue nonstop for weeks to come with calls from hundreds of concerned people around the country from all walks of life who wanted to help Japan in some way.

In retrospect, it seems remarkable that the trends that became evident that first day—March 11, 2011—would hold true throughout the American public’s response to the disaster that became known in Japan simply as “3.11”—the 9.0 magnitude earthquake, the towering tsunami, and the chilling crisis that unfolded afterward at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. The response was overwhelming, highly diverse, and largely based on people’s personal connections to Japan, whether through travel or work, participation in some Japan-related activity, or memories of a Japanese exchange student they had known as a child. Moreover, the intensity of emotion and the compassion that many Americans felt toward Japanese victims seemed to be magnified by the shocking footage they saw on television and the Internet and then further amplified by social media.

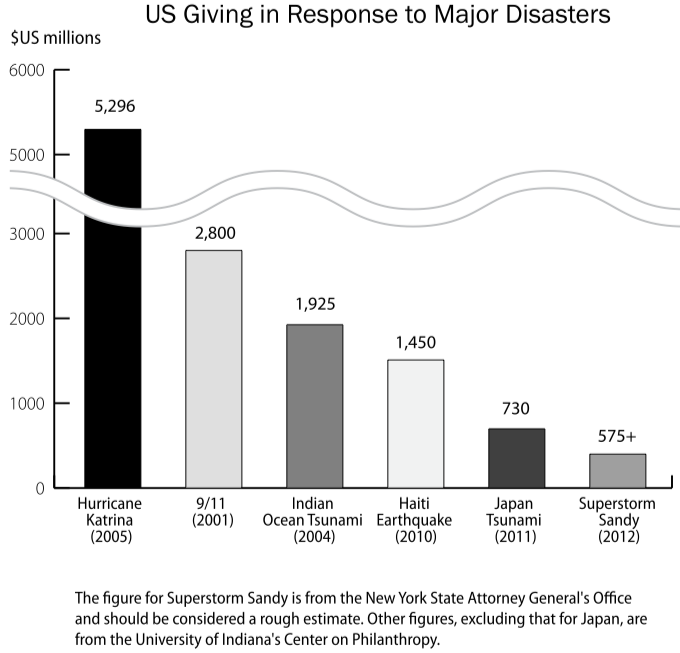

In a pattern that was to be repeated around the world, Americans in all corners of the country mobilized to demonstrate their solidarity with Japan and raise funds for the disaster response. In the end, they donated nearly three-quarters of a billion dollars for a broad range of rescue, relief, and recovery efforts—the greatest outpouring of charitable donations ever for an overseas disaster in another rich country.1 Remarkably, this ranked as the fifth most generous incidence of private giving in US history for any disaster, trailing only the responses to Hurricane Katrina, the 9/11 attacks, the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, and the 2010 Haiti earthquake. The story of how this extraordinary response played out reveals a great deal about the trends that have been reshaping disaster philanthropy in recent years and yields vital lessons for future responses to megadisasters, especially in other developed countries.

In a pattern that was to be repeated around the world, Americans in all corners of the country mobilized to demonstrate their solidarity with Japan and raise funds for the disaster response. In the end, they donated nearly three-quarters of a billion dollars for a broad range of rescue, relief, and recovery efforts—the greatest outpouring of charitable donations ever for an overseas disaster in another rich country.1 Remarkably, this ranked as the fifth most generous incidence of private giving in US history for any disaster, trailing only the responses to Hurricane Katrina, the 9/11 attacks, the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, and the 2010 Haiti earthquake. The story of how this extraordinary response played out reveals a great deal about the trends that have been reshaping disaster philanthropy in recent years and yields vital lessons for future responses to megadisasters, especially in other developed countries.

The Growing Roles of NGOs and International Disaster Philanthropy

The story of the response to the Great East Japan Earthquake is a profoundly human one, and one that encompasses the experiences of millions of people. The mayor who spent a snowy night stranded on the roof of city hall watching his city be swept away, then felt compelled to work around the clock for weeks to direct rescue operations without taking time to grieve with his two sons or to search for his wife who went missing in the waves. The young woman who accepted her colleague’s offer to cut in front of him on the stairs while fleeing the rising waters and now struggles with guilt after being the last person to make it out alive. The volunteer who gave up a comfortable job in Tokyo to find new meaning in life running a nonprofit aid center in the disaster zone. The California couple who were so moved by the suffering that they decided to refuse wedding gifts and instead urge their guests to make donations in their honor to a relief fund.

But it is also part of a larger story about the globalization of disasters and the growing role of nongovernmental actors in disaster responses. The massive outpouring of US giving for Japan is important not just as a reflection of the goodwill that one country’s people harbored toward another’s, but also because it signifies how the nongovernmental sector’s response increasingly has the capacity to alter the course of a disaster recovery half a world away. While the public perception is that national governments and UN agencies lead the international response to megadisasters, the role of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and private donations has been expanding for some time. This trend was already apparent in the international response to the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, when nearly 40 percent of the $14 billion in pledged overseas aid came from private donations (Flint and Goyder 2006, 15). Similarly, data from the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs indicates that nearly 40 percent of all overseas pledges after the Haiti earthquake—and 50 percent of commitments disbursed to date—were from private donors, although this likely undercounts total private giving for the disaster (UN OCHA, “Haiti Earthquakes” 2013).2 But the role of private giving became even more pronounced in the overseas response to 3.11, as private sector donations have quietly outpaced official government aid for Japan.3

Of course, any retelling of the American response to 3.11 must start with the rapid military response, one that was brilliantly named Operation Tomodachi, incorporating the Japanese term for “friend.” US forces stationed in Japan began mobilizing within hours; 24 naval vessels, including an aircraft carrier, were positioned off the Tohoku coast while US spy planes flew data-gathering missions over the nuclear plant; and 24,000 American service members became involved in the relief efforts, many of them working alongside Japanese Self Defense Force troops in the disaster zone, clearing rubble, transporting emergency supplies, and aiding survivors (Feickert and Chanlett-Avery 2011, 1). Stateside in Washington DC, a broad range of government agencies sprang into action to coordinate government agencies’ provision of aid, support US residents in Japan, and undertake the increasingly critical task of advising the Japanese government—and pressuring it to move more decisively—in its halting response to the nuclear crisis.

Still, the nongovernmental response from the United States was equally impressive and, in some ways, even more astounding. The $730 million4 in US private donations dwarfed the $95 million that the US government is estimated to have spent in helping Japan, although it bears noting that the specialized capabilities that the US military and other government agencies brought to the response cannot be quantified solely in financial terms (JCIE 2014; Feickert and Chanlett-Avery 2011, 1). The prominence of nongovernmental actors on the donor side was matched by the expanded role that Japanese NGOs played in the response, filling the gaps in the national and local governments’ provision of services essential for relief and recovery to an extent that is unprecedented in Japanese history. This helped to make 3.11 one of, if not the, first major disasters in modern history when the nongovernmental sector played as crucial of a role in the international response as governments and international organizations.

The US Nongovernmental Response

In the initial days after 3.11, a diverse range of American groups began weighing how they could help without placing a greater burden than necessary on local authorities and frontline responders. The fact that the disaster had struck such a rich country with considerable resources and extensive experience dealing with large-scale disasters made it even more challenging to identify precisely what they should be doing. While a few of the NGOs that normally respond to disasters scrambled to put staff on the Friday morning flights to Japan—even with little idea of how to proceed once they landed in Japan—most of the major humanitarian assistance organizations took a more restrained posture of monitoring the situation and consulting with Japanese authorities about what gaps they could fill. A handful even debated whether it was appropriate to raise funds for the response, and Doctors Without Borders and a few other groups initially declared that they would not accept donations specifically earmarked for Japan until they had a clearer picture of how much need there would be for their assistance. However, for many groups, especially the major humanitarian assistance organizations accustomed to raising large amounts of funds in the immediate aftermath of disasters, the default stance was to start a relief fund. Within the week, hundreds of major organizations were launching fundraising drives, even though many had not decided whether to use them to support their own relief activities or to re-grant the contributions to Japanese groups.

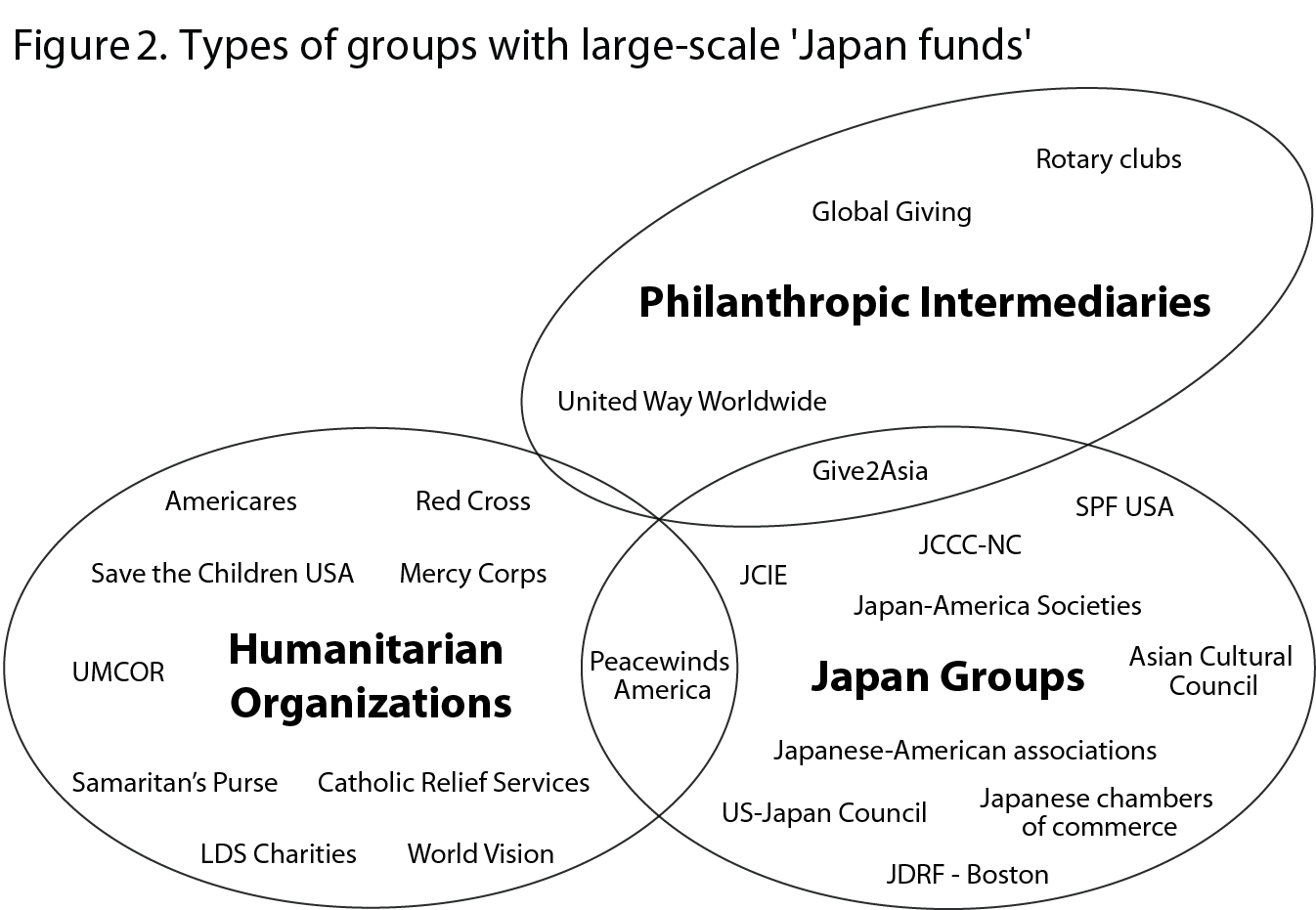

In those chaotic first days, it became apparent that there were at least three distinct sets of organizations active at the national level in the United States, and while there was some overlap, by and large, the groups that fell into one set had little awareness of what others in different circles were doing. One set consisted of the professional humanitarian assistance and disaster relief organizations that are accustomed to mobilizing rapidly to dispatch assessment teams and deliver aid for crises around the world. These included, for example, the American Red Cross, World Vision, and Mercy Corps. A second, smaller set involved international philanthropic intermediaries, organizations that specialize in collecting donations and then re-granting them overseas. This encompassed more traditional groups like the United Way, as well as some new, tech-savvy organizations such as Global Giving that have sprung up to facilitate online giving. The third set, meanwhile, consisted of Japan-related organizations in the United States, ranging from the national network of roughly 40 Japan-America Societies to policy-oriented institutes and charitable foundations that support US-Japan exchange.

Each of these groupings had their own particular strengths and shortcomings. The professional humanitarian assistance organizations had a deep understanding of what was required to respond at the different stages of disasters. They had a playbook for what to do on Day 1, Day 3, and Day 10; knew how to anticipate the transitions from rescue to relief and from relief to recovery; and had a good feel for how needs were likely to change at each stage. They also had mechanisms in place that allowed them to launch major fundraising appeals on a moment’s notice—website templates, lists of major donors, and what can be called brand name recognition among the general public.

Each of these groupings had their own particular strengths and shortcomings. The professional humanitarian assistance organizations had a deep understanding of what was required to respond at the different stages of disasters. They had a playbook for what to do on Day 1, Day 3, and Day 10; knew how to anticipate the transitions from rescue to relief and from relief to recovery; and had a good feel for how needs were likely to change at each stage. They also had mechanisms in place that allowed them to launch major fundraising appeals on a moment’s notice—website templates, lists of major donors, and what can be called brand name recognition among the general public.

However, most of these groups also had limited knowledge of Japan and few connections to the Japanese government officials and humanitarian aid groups that were taking the lead in the response. Things proved particularly challenging because these organizations were accustomed to operating in developing countries, where donor coordination mechanisms utilized to share information among groups distributing development aid could quickly be repurposed to facilitate NGO coordination on the disaster response. In Japan, though, there was no natural contact point for overseas organizations that needed both connections to other organizations and a crash course on how to operate in its unique societal milieu, as well as no obvious convener that could facilitate coordination with the dozens of other Japanese and overseas groups that were rushing to help. While two groups, Japan Platform and the Japan NGO Center for International Cooperation (JANIC), eventually took on some of these functions, they remained imperfect vehicles for this purpose.

Meanwhile, the second set of organizations that mobilized—the philanthropic intermediaries—had a strong grasp on what was required to raise funds that could be re-granted to overseas organizations and how to do this in a deliberate and sustainable manner. This made them particularly well suited to support the Japanese nonprofit organizations that would be relied upon to play key roles in the long-term recovery process. Also, they had a good understanding of the often undervalued art of grant-making, meaning that they recognized the importance of working in a collaborative manner with funding recipients to encourage them to formulate viable project plans, structured the funding process in a way that did not test the limits of already overstretched Japanese groups, and insisted on injecting appropriate accountability and transparency requirements into funding proposals and grant agreements.

However, while they had a deep understanding of international grant-making—as well as the intricacies of domestic tax law that pertain to it—they had a much weaker comprehension of the practices commonplace in Japan’s nonprofit sector, which was far less professionalized than in other developed countries. Fortunately, though, the three key philanthropic intermediaries that were most active in the disaster response—Global Giving, Give2Asia, and United Way Worldwide—happened to have special ties to Japan. Global Giving, which heretofore had focused on supporting development projects in poor countries, was headed by a dynamic Japanese expatriate, Mari Kuraishi, who had a personal stake in helping her country. Give2Asia, meanwhile, had been spun off of the Asia Foundation and was designed to channel funds to nonprofit initiatives in Asia, so it had historic ties to Japan as well as staff members with experience living in the country. Meanwhile, United Way Worldwide, the Virginia-based parent organization for the United Way affiliates in the United States and around the world, had long cooperated on small-scale initiatives with the Central Community Chest of Japan.

For their part, the third set of organizations that became particularly prominent in the philanthropic response, a broad mélange of institutions dedicated to various aspects of US-Japan exchange, had hard-earned insights into the dynamics of Japanese society and strong networks at the national and local level in the country. Their staff also had a deep personal commitment to working with Japan, they tended to have language skills that enabled them to go beyond English-speaking circles to access a much broader range of information and people, and they often had a base of constituents with a deep interest in Japan and a desire to donate money and time to help.

Yet they, too, were forced to grapple with serious shortcomings. Their intimate knowledge of some aspects of Japanese society did not necessarily extend to a deep understanding of how Japan’s nonprofit sector operates. Moreover, with a few exceptions, they had little experience with international grant-making and were forced to spend valuable time on basic steps such as learning how to create application forms that would elicit crucial information from potential grantees but avoid burdening them during a time of crisis, consulting with lawyers about how grant agreements could be structured to meet US tax requirements and post-9/11 anti-terrorism mandates, and creating orderly processes to evaluate potential funding recipients. They also had to learn the basics of disaster responses on the fly. In some instances, decisions that groups made in the initial hours and days—for example, to announce that they would set aside management fees from incoming donations and would channel 100 percent of funds raised into the disaster zone—later created significant burdens for them when far more money than anticipated flowed into their coffers. Finally, since they were, by and large, small organizations with tight budgets and limited staff, their institutional capacity was strained by the added burden of managing disaster funds, a particularly ironic development since one of their major concerns in evaluating candidates for funding was the limited institutional capacity of the Japanese NGOs working in the disaster zone.

Who is Coordinating This Thing?

Even though the disaster dominated national news for weeks and hundreds of groups were launching major disaster responses, there was no concerted effort to forge a coordinated national response in the way that had been done for other recent megadisasters. After the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, former presidents Bill Clinton and George H. W. Bush famously stood at a White House press conference alongside President George W. Bush, where they urged Americans to give generously to US humanitarian groups involved in relief efforts. A similar tack was taken for the 2010 Haiti earthquake, when Clinton and George W. Bush were asked by President Barack Obama to play a leading role in mobilizing Americans to support the response, inspiring them to launch the Clinton-Bush Haiti Fund and keep the issue of Haiti relief in the public spotlight by taking several high-profile trips to the country. In the case of Japan, however, no national figures were tapped as focal points for mobilizing the philanthropic response, no real attempt was made to organize a national benefit concert, and no comprehensive information-sharing effort succeeded in reaching the full range of nongovernmental organizations launching “Japan funds” and pledging aid.

Part of the reason for the lack of coordination at the national level can be ascribed to the sheer number and diversity of organizations that mobilized in an organic fashion for the response. One stunning statistic that illustrates the diversity of efforts is the fact that 46 different nonprofit organizations each raised more than $1 million for relief and recovery efforts. More than 120 gathered over $100,000 a piece—notably, only a small portion of them specialized in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, and over one-third had no prior experience fundraising for disaster responses (JCIE 2014).5

But the sheer number of players was not the whole story. While American humanitarian groups have considerable experience responding to disasters in developing countries, there was no recent precedent for assisting a developed country with such a massive disaster. This sparked debates over whether it made sense to try to aid another rich country and, if so, how to best do this. A spate of articles penned by commentators who were perhaps well intentioned but woefully uninformed about Japanese society and the real needs on the ground came out cautioning Americans against donating for the disaster response in a country that arguably had sufficient resources to take care of itself.6 While this provoked considerable handwringing among the groups working around the clock to support their Japanese compatriots, these arguments ultimately had less impact on the response than the lack of clarity about who, if anybody, should be taking the lead in responding.

Ultimately, the coordination that did take place on the national level ended up happening within the distinct circles of groups and not between them. The US Agency for International Development (USAID), the lead government agency for overseas humanitarian crises, and InterAction, the Washington DC–based umbrella organization for US humanitarian assistance and disaster relief NGOs that work internationally, quickly began sharing information with each other, as well as with the US Chamber of Commerce Business Civic Leadership Center. These three organizations formed a hub that relayed information among the US government, big business, and the major humanitarian assistance groups. However, there was no effort to reach out to the US-Japan organizations, at least those outside of the Washington DC area, or to most of the philanthropic intermediaries.

Simultaneously, there were multiple efforts to share information among US-Japan exchange organizations, Asian-American groups, and a handful of organizations for Japanese expatriates. These included initiatives spearheaded in the first week after the disaster by the Japan Center for International Exchange and by the US-Japan Council to convene meetings and disseminate information online for NGOs involved in the philanthropic response. There were also a number of more discrete efforts; for example, the National Association of Japan-America Societies regularly kept its member organizations informed, the Japan Society of New York periodically convened a small set of NY-based organizations for roundtables to share information, and local initiatives emerged in Seattle, New Orleans, and elsewhere around the country.

Even though some of the efforts among Japan-related groups grew to be quite large, involving dozens of organizations, they tended to operate in an ad hoc manner, depending heavily on personal connections. And there was no systematic exchange of information with the humanitarian groups that were having separate discussions among themselves, although, by chance, some of the major philanthropic intermediaries, namely Give2Asia and Global Giving, were eventually brought into the Japan-related organizations’ coordination efforts. The lack of communication between the circles of humanitarian assistance organizations and Japan-related groups was not because either side wanted to exclude the other but simply because they were hardly aware of what each were doing.

Unsurprisingly, this lack of awareness about what other groups were doing extended to the international realm as well. Even before American groups started trying to bring some coordination to their efforts, internationally minded Japanese NGOs in the disaster relief field had started meeting in various forums in Tokyo and elsewhere, most notably under the aegis of Japan Platform and JANIC. Yet most American groups were barely aware that these discussions were taking place and, even after the first several months had passed, there was little flow of information across the Pacific about what was being discussed in the various forums.

A Grassroots Phenomenon

While the larger humanitarian groups, philanthropic intermediaries, and Japan-related organizations were working to formulate their responses, a more organic movement was brewing at the grassroots level. In the initial days and weeks after the disaster, the media had started reporting on the reluctance of Americans to donate generously to help Japan, contrasting it with the outpouring of giving after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and the 2010 Haiti earthquake. USA Today blared “US Donations Not Rushing to Japan” and ABC News asked “Americans Less Generous in Disaster Relief?” Of course, the circumstances were very different. Japan was a rich country that was well prepared to deal with disasters while Haiti and the Asian countries struck by the 2004 tsunami were much poorer, so it stood to reason that the humanitarian groups and faith-based organizations that normally mobilize for disasters in developing countries would not see the same inflows of charitable donations. But, still, the headlines did not jibe with what was unfolding around the country.

One of the first hints that something different was happening was the scene that played out in New York City six days after the disaster, on March 17. Naoko Fitzgerald, a young Japanese mother of two, had emailed a call to action urging her other friends, most of them also Japanese expatriates, to join her in Manhattan’s Union Square that afternoon to show support for her country’s people and collect donations. She expected maybe one or two dozen friends to join her but was taken aback when the square quickly filled up with hundreds of Japanese and American mothers wearing kimonos, wheeling baby strollers, and carrying signs that read “Help Japan,” and “Pray for Japan.”

As they stood on the sidewalks with donation boxes, green-clad St. Patrick’s Day revelers who had been celebrating at the parade farther uptown started to stream down Broadway. That is when the second surprise came. What could have been a recipe for an embarrassing alcohol-fueled display of cultural insensitivity instead turned into a bittersweet spectacle, as passersby walked up to the mothers to offer pocket change, words of comfort, and in some cases tearful hugs. When the mothers and children combined the contents of their donation boxes, it turned out they had collected more than 30 pounds in coins and small bills in a matter of three hours—a total of $11,204. Americans really were giving.

Similar scenes played out around the country as thousands of schools, churches, and community groups conducted fundraising drives. In many instances, these were inspired by personal ties. Japanese-American organizations, which traditionally had kept low public profiles, took the lead in launching fundraising campaigns in communities around the country. Americans who had lived and worked in Japan, including the 26,000 alumni of the Japan Exchange and Teaching Program, could be found behind the scenes of many of the major fundraising initiatives that were started at corporations and nonprofit organizations that were not normally identified with Japan. Meanwhile, at least 95 municipalities with sister cities in Japan launched fundraising drives of their own, collecting a combined total of more than $2.4 million to support relief efforts (Menju and Geiger 2012). And hundreds of anime fan clubs, karate schools, university Japan clubs, and other small groups devoted to some aspect of Japanese culture started their own relief funds. It turned out that the grassroots ties between the two countries were deeper and more diverse than most people realized.

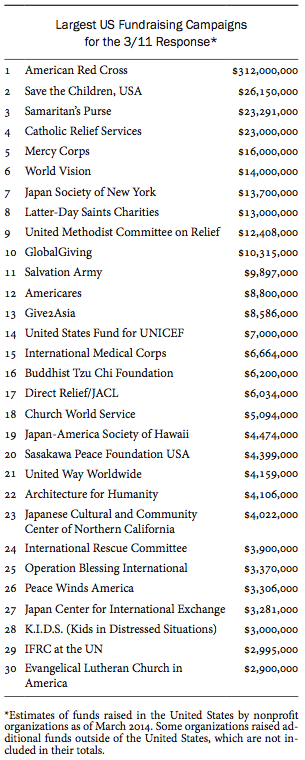

However, this upsurge of philanthropy did not register in the early tallies of US donations, giving rise to the media narrative that the US public response was muted. This was because the thousands of small groups that were at the forefront of the fundraising effort were operating below the radar screen of the national media, which was accustomed to surveying the top 10 or 15 humanitarian organizations that traditionally collect the vast bulk of donations for any given overseas disaster. This time, though, people were donating to a much broader range of groups, often smaller ones close to home, and these groups were taking their time to deliberate over how they could most wisely channel the funds they had collected to Japan. A remarkable number of groups, more than 330 in all, found ways to give funds directly to Japan, mainly to Japanese NGOs working in the disaster zone (JCIE 2014). The others donated the proceeds of their fundraising drives to other, larger US groups, which in some case fed them to the even larger organizations that eventually disbursed them to Japan. (The table to the right shows the organizations with the largest US fundraising campaigns, although in almost all cases they are the beneficiaries of many smaller organizations that regranted funds to them.)

However, this upsurge of philanthropy did not register in the early tallies of US donations, giving rise to the media narrative that the US public response was muted. This was because the thousands of small groups that were at the forefront of the fundraising effort were operating below the radar screen of the national media, which was accustomed to surveying the top 10 or 15 humanitarian organizations that traditionally collect the vast bulk of donations for any given overseas disaster. This time, though, people were donating to a much broader range of groups, often smaller ones close to home, and these groups were taking their time to deliberate over how they could most wisely channel the funds they had collected to Japan. A remarkable number of groups, more than 330 in all, found ways to give funds directly to Japan, mainly to Japanese NGOs working in the disaster zone (JCIE 2014). The others donated the proceeds of their fundraising drives to other, larger US groups, which in some case fed them to the even larger organizations that eventually disbursed them to Japan. (The table to the right shows the organizations with the largest US fundraising campaigns, although in almost all cases they are the beneficiaries of many smaller organizations that regranted funds to them.)

The lag time that resulted from this chain of giving meant that sizeable donations were still coming into organizations playing major roles in the disaster response six months and even one year after the disaster. It also obscured the fact that nearly three-quarters of a billion dollars had been donated, much of it in a spontaneous and organic manner. Fortunately, the grassroots nature of the response had another unintended benefit. The delays in getting funds into the disaster zone meant that a sizeable portion of the donations raised in the United States could be used for long-term recovery efforts rather than for immediate rescue and relief. The Japanese government and private sector had sufficient domestic resources to support much of the initial relief activities that were needed, so it was a boon that additional monies would be available for the recovery stage, when funding often dries up.

The Drivers of American Giving

The sheer amount of donations raised in the United States for the disaster—at least $730 million over the first three years—indicates that something important has changed in terms of how Americans respond to disaster. Of course, this is not merely an American phenomenon. While the United States has been the origin of the most overseas private donations for Japan, there were similarly extraordinary responses from many other countries as well. Taiwanese donors reportedly made roughly $235 million in contributions, making Taiwan the second largest source of overseas private giving for the 3.11 response.7 Despite long-standing historical animosities, South Koreans also donated record amounts for the relief and recovery efforts (Yonhap News 2011), and Canadians, British, and people in many other countries had similar reactions.

It was not just the amount raised in aggregate that increased; the funds donated to many individual organizations also far exceeded expectations. For instance, the staff of the Japan Society of New York created a disaster relief fund after the 1994 Great Hanshin Earthquake killed more than 6,400 people in Kobe and, when all was said and done, it raised roughly $75,000. Seventeen years later, when they launched their new Japan Earthquake Relief Fund, they anticipated some increase in giving but never expected to raise more than 180 times that amount—a total of $13.7 million.8

One factor that surely contributed to the extraordinary outpouring of charitable contributions is the gradual rise of a culture of disaster giving. In recent years, Americans have become accustomed to making donations to help with disasters that receive prominent media attention. It is easy to see how this can become self-reinforcing, building up expectations that donations should be made after subsequent major disasters. Numerous studies show that disaster giving tends to be made on impulse, so these expectations combined with the increasing ease with which people can quickly donate online or through text messages and other media seems to have driven a shift in Americans’ thinking about what they should do when they learn of a major tragedy.9 Therefore, it should be no surprise that four of the five largest outpourings of US private giving in response to major disasters have all taken place in the last decade and all five have occurred since 2001.

As noted earlier, a second important driver of the Japan response was the strength of people-to-people connections and grassroots ties at different levels of the US-Japan relationship. A third was surely the enormous scope of the disaster, which was by far the most devastating to strike a developed nation. The magnitude of 3.11 and its superlative nature—the tsunami waves were higher than people had imagined was possible, the drama surrounding the efforts to prevent a full meltdown at the Fukushima nuclear plant was more chilling than any Hollywood movie—encouraged people to donate who may have been less willing to do so for a large but less shocking disaster.

A fourth major factor appears to have been the advance of communications technology, particularly the Internet, digital technology, and social media. In addition to increasing the ease of giving, these brought an immediacy to the disaster that turbocharged the philanthropic response. While personal ties made the disaster significant, the ubiquity of heartbreaking news and apocalyptic images helped convince people that they needed to do something to help. Being able to click on YouTube and watch cell phone videos shot from rooftops while the waves rose menacingly from below gave the disaster a raw emotional resonance that was barely conceivable in the era of print media.

The disaster response was also different because of Japan’s status as another advanced, post-industrial society. On the one hand, this led some to refrain from donating and compelled many humanitarian organizations to hesitate about launching all-out funding appeals. However, on the other hand, it seems to have encouraged donors who might otherwise not have given. One reason is that grassroots ties between the two nations were arguably more robust because of the similar levels of development of both countries. Another equally significant factor is the strong economic relationship that has developed between Japan and the United States. Thousands of American companies have business ties to Japan, owning subsidiaries there, serving as subsidiaries of Japanese companies, counting Japanese companies as important clients, or depending on Japanese suppliers. The human relationships developed through these business interactions, as well as the desire to be perceived in Japan as aiding in the country’s time of need, drove many companies to make the kinds of generous donations that may not have been forthcoming for a similar disaster in a remote, poor country. In the end, more than 50 US companies pledged over $1 million for the disaster response, a remarkable number by any measure (JCIE 2012).

Assessing the US Nongovernmental Response

First and foremost, any assessment of the American response needs to weigh how much of a difference US support made on the ground. Considering the key role that the Japanese nonprofit sector has played in the disaster response, the massive amount of US private giving was guaranteed to have a sizable impact if directed effectively. But the nature of the overall flows into the nonprofit sector in Japan has meant that this impact has been even more pronounced and beneficial than one might assume at first glance.

This is because, while the nonprofit sector in Japan has been expanding from a relatively low base, a culture of giving for nonprofit activities has yet to develop deep roots and thus domestic philanthropy has not kept up with the demand from nonprofit organizations. Although domestic giving for the disaster soared to record levels, totaling an estimated ¥600 billion (US$6.7 billion) by September 2012, nearly 85 percent went to local government agencies and the country’s traditional gienkin funds that distribute cash payments as compensation to disaster survivors and the family members of victims (Japan Fundraising Association 2012, 22).10 Japanese companies and individuals are still unaccustomed to supporting nonprofit organizations, so only a small fraction of donations—less than 10 percent by some accounts—went for nonprofit activities (Japan Fundraising Association 2012, 22).

In contrast, nearly 90 percent of US donations were earmarked for nonprofit activities, a total of roughly $660 million (JCIE 2014).11 While it is difficult to get a clear picture of the overall size of the pool of donations available to Japanese nonprofits working on the response, a rough estimate is that, at least for the initial two years, US donors ended up accounting for as much as one-quarter to one-third of total private giving to support the Japanese NGO response to the disaster—a remarkable share by any measure.12 Considering the key role that Japanese NGOs have played, it seems clear that American contributions have helped to fill an important gap.

Of course, a flood of money to NGOs is not always a good thing. After the Indian Ocean tsunami, the Tsunami Evaluation Coalition criticized the “second tsunami” of aid organizations that rushed to the scene to implement programs despite having little or no experience or capacity to follow through on their commitments (Cosgrove 2007, 16). This is always a risk in international crises, but this time almost all of the US donors sought to disburse the funds they raised by re-granting them to Japanese organizations or by working in close cooperation with local partners. This was not solely because they had learned from past mistakes but also because it was much more daunting to parachute into a developed country and try to directly implement programs, especially in a nation like Japan that has such high linguistic and cultural barriers. As a result, it seems that US funding gave rise to few of the negative, unintended consequences that are often seen in other disaster responses.

In a sense, a “second tsunami” did occur, but it came in the form of the numerous Japanese NGOs with no prior expertise in disaster-related issues that rushed to help and the hundreds of new nonprofit organizations that were established by Japanese volunteers. This had little to do with overseas funding, however. Given the deep desire of ordinary Japanese to do something to help, the surge of unskilled domestic NGOs into the disaster zone would have happened regardless of the availability of overseas funding. While some of these groups launched overlapping (and sometimes marginally useful) activities, on balance most managed to play a positive role in advancing the relief and recovery efforts and many proved to be indispensible. Moreover, being Japanese, they could more easily be brought into local coordination initiatives and had the linguistic and cultural understanding that enabled them to be more responsive to local needs and desires than overseas groups could have been.

Another sign that US funding was being directed wisely was the fact that most donations took the form of cash rather than in-kind goods, which accounted for about 2 percent of total US giving (JCIE 2013a). In the early days, there was a scramble among some American organizations to ship food, medical supplies, gasoline, and even socks to Japan; however many of these efforts were quickly aborted after Japanese government authorities and disaster professionals stressed that the issue on the ground was not a domestic shortage of supplies but rather the destruction of the local transportation infrastructure and distribution networks.13

Challenges for Donors and Recipients

While the outpouring of American giving has been overwhelmingly beneficial for Japan and has filled a critical niche, both US organizations collecting funds and Japanese ones utilizing them have faced numerous challenges along the way. In the early days, it looked as though one major problem would be the gold rush of concerned groups and individuals that were launching fundraising campaigns with little idea of how to effectively distribute the proceeds. However, this eventually sorted itself out as many of these groups decided to funnel their funds through organizations with greater capacity to direct them to worthy Japanese NGOs.

But even when these funds were handed off to more professionalized organizations, the lack of understanding about the terrain of the Japanese nonprofit sector and the dynamics of international grant-making was a major hurdle. While each of the major sets of organizations playing prominent roles in the response—the humanitarian assistance organizations, philanthropic intermediaries, and Japan-related groups—had a good grasp of their own area of expertise, almost none of them started out with the whole picture; nor was there sufficient coordination across the circles to allow them to easily remedy their weaknesses. Instead, each organization had to learn, largely on its own, how best to go about providing aid in Japan.

One of the major complaints that quickly arose among US organizations trying to support Japanese NGOs involved the difficulties they faced in identifying appropriate institutions and soliciting grant request from them. In a June 2011 conference convening many of the larger Japan-related organizations and philanthropic intermediaries in the United States, the head of one major philanthropic intermediary exclaimed that in all of her years of trying to facilitate funding to nonprofit organizations in countries around the world, she had never before seen a situation in which it was so difficult to find organizations willing and able to take their money.14

Part of the problem arose from American organizations’ lack of familiarity with the Japanese nonprofit sector as well as large gaps in expectations on both sides. But there were also more complicated issues at play that stemmed from the underdeveloped state of Japan’s nonprofit sector, at least relative to what was common in other developed countries. Many US organizations were unwilling to disburse funds—and in fact, they were legally prohibited from doing so—without fully vetting the Japanese recipients, receiving a viable project plan, signing a funding agreement, and requiring regular reporting and accountability. In short, they were committed to making professionalized grants (or what is called joseikin in Japanese). But many Japanese organizations had little experience with grants and, with so much domestic funding with few strings attached sloshing around the disaster zone in the early days, it was easier to focus on receiving straightforward donations (kifukin) that they could use however they wished without sticking to a predetermined project plan or providing detailed reporting.

In almost all instances, the main issue was not that Japanese organizations were irresponsible or trying to avoid accountability; rather, most tended to be overly diligent in respecting the desires of the donors. But they were woefully understaffed and the one or two senior figures who could deal with overseas organizations—and even Japanese funders—were making heroic efforts, working 16 to 18 hour days, seven days a week, for months on end just to keep resources flowing to the people carrying out programs on the ground. The mismatch in capacity with US organizations was stark, even though many Americans were unaware of how just how unbalanced things were.

To take one example, the Central Community Chest of Japan and its annual “red feather” campaign is recognized by practically every ordinary Japanese, and the group fulfills a role in Japanese society that is analogous to that of the United Way in the United States. It has long played a key role in disbursing funds after domestic disasters, and it has historic ties to United Way Worldwide, the US-based umbrella group for the United Way network, so it was natural for United Way Worldwide to channel the funds it raised for the 3.11 response to the Central Community Chest. But even though the Central Community Chest is one of Japan’s most established organizations in the nonprofit sector, it operates with just 16 full-time staff. This stands in stark contrast to the United Way Worldwide, which has more than 260 staff. If such vast disparities can arise in the relationship between one of the most established organizations in the Japanese nonprofit sector and its longtime partner, it is easy to imagine how dealings between other overseas and Japanese organizations could be even more unbalanced and how smaller Japanese groups, facing overwhelming demands on their time, would have a preference for the funding with the least paperwork.

The limited institutional capacity of Japanese NGOs was not just an issue of size, and it proved to be one of the most critical challenges for overseas donors trying to support relief and recovery efforts. Most of the staff working at Japanese NGOs have limited experience in program planning, project management, and the other specialized tasks that are essential for major nonprofit organizations’ operations. This is a product of the underdevelopment of the country’s nonprofit sector and the weak financial base of most of its nonprofit organizations, which obliges senior staff to cover a broad range of duties that might otherwise be left to more junior staff were there funds to hire them. As a result, the people who could otherwise focus primarily on serving as liaisons with overseas organizations or on devising and drafting sophisticated project plans tend to be spread far too thin on a broad range of tasks. This problem was further exacerbated by a Japanese work culture that relies heavily on time-consuming, face-to-face meetings and a lack of awareness on the part of US groups of how much of a disruption requests for even relatively simple documentation could cause for Japanese NGO staff trying to juggle so many other tasks. Going beyond these more immediate issues, the tenuous financial situation of many Japanese NGOs and the overall weakness of the philanthropic sector in Japan also called into question the long-term sustainability of programs, even if they could be launched with overseas money.

In the face of these challenges, one of the keys to the quick and effective disbursement of the funds was the presence of preexisting relationships between American donors and Japanese NGOs. These made it easier for overseas organizations to disburse funds in a timely manner and also helped smooth over tensions when problems inevitably arose. As one program officer at a major American donor organization remarked, even though their grantee was not providing timely activity reports as promised, “we have faith in their leadership because we have worked with them for so many years and know they will deliver in the end.”15

However, the number of US donors with prior ties to Japanese organizations involved in the disaster response was surprisingly limited. A number of faith-based organizations, such as Catholic Relief Services, Latter-Day Saints Charities, and the Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA), had longstanding ties to their Japanese counterparts from the same religious tradition (Caritas Japan, the Japanese branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, and ADRA Japan), and a handful of humanitarian assistance organizations such as the American Red Cross, Save the Children USA, and World Vision had affiliates in Japan as part of their global networks. But outside of linkages with groups that were often perceived as Japanese branches of Western organizations, there were few strong ties between independent American and Japanese humanitarian groups. (The relationship between Mercy Corps and Peace Winds Japan, which motivated Mercy Corps to raise funds specifically for Peace Winds Japan in the early days is perhaps the only prominent exception.) This held true for many of the philanthropic intermediaries, too, and even for the Japan-related organizations, which were generally unfamiliar with the types of Japanese organizations that were skilled enough to carry out relief and recovery activities. This lack of pre-existing ties led Stacey White, an American expert on natural disasters, to lament in a New York Times opinion piece five days after the disaster that just yesterday, I found myself on a conference call with a group of smart and well-intentioned people seeking to help Japan at this critical time. At one point during the conversation, someone asked how she might connect not just with US aid entities and international nongovernment organizations, but directly with Japanese businesses and civil society groups. There was silence. No one seemed to know (White 2011).

Not only were the networks that could be activated for the disaster response surprisingly thin, but the strains of responding to 3.11 exposed serious fault lines in many of the partnerships that predated the disaster and severely tested the new ones that were forged afterward. Wide gaps in expectations, vastly differing communication styles, cultural misunderstandings, a lack of institutional capacity among Japanese NGOs, and the strain of the intense time commitment needed to maintain strong partnerships fed disillusionment on both sides. This compelled many of the US organizations attempting to distribute funding for the disaster response to give up on their initial thoughts of channeling money through Japanese intermediaries or disbursing it solely to one organization and, instead, to carve out a more active role in identifying and evaluating grantees. In many instances, they ended up dispatching representatives to Japan on a temporary basis to oversee the distribution of their funds rather than entrusting this to a Japanese partner. In the end, while many American and Japanese organizations involved in the 3.11 response eventually found ways to make partnerships work, the challenge of keeping them effective and balanced has remained a lingering problem.

A final challenge that US organizations and their Japanese partners are starting to face involves the funding bubble that has developed in the disaster zone. In the initial months after the disaster, the outpouring of charitable contributions from home and abroad was stunning. One report found that 77 percent of Japanese adults gave funds—an extraordinary rate for a country said to have a weak culture of giving (Japan Fundraising Association 2012, 23). Another revealed that 95 percent of major Japanese companies made cash donations, 72 percent provided in-kind contributions, and 56 percent had employees who volunteered with relief efforts (Keidanren 2012). But as is common in such cases, the funding was front-loaded, and after the massive inflows of 2011, donations started to taper off. By the summer of 2012, nonprofit organizations throughout the disaster zone were talking about the declines they were seeing in funding and the steeper drops they expected to come. To their credit, many of the large donors from the United States and elsewhere allocated their funds for multiple years. However, by the end of the second year, in early 2013, almost all US groups were facing pressure from their boards, donors, and other stakeholders to finalize the allocation of their funds and prepare to exit the scene. This was especially true for the organizations that had strayed from their core missions in operating relief funds for Japan, which entailed virtually every major American group involved in the 3.11 response. These pressures were natural, and even healthy, but they just further steepened the downward slope on the far side of the bubble, adding to the threat to the sustainability of all the new programs that had been launched in the disaster zone by Japanese NGOs.

Lessons from 3.11

As with any crisis, there are many lessons to be drawn from the 3.11 response about what to anticipate for future megadisasters in developed countries and how we might react more effectively next time. Fortunately, this has been a story with no villains, only heroes. All of the major protagonists comported themselves as best as they could, and many acted with remarkable compassion, dignity, and wisdom. American organizations typically went out of their way to respect the desires and prerogatives of local Japanese groups, and they adapted their approaches repeatedly in a highly fluid and complex environment in order to better meet real needs on the ground. Meanwhile, Japanese NGOs did more than seemed possible given their institutional limitations, their leaders consistently made extraordinary personal sacrifices to sustain their organizations’ responses, and most demonstrated considerable grace and patience in dealing with well-intentioned foreign donors whose preconceptions did not always align with realities on the ground.

Surprisingly, although it seems de rigueur for disaster responses, there have not even been any major nonprofit scandals so far; no NGO executives have been caught lining their pockets and no major misuses of charitable funds have come to light.16 In fact, the most prominent “scandal” involved a Japanese man who was arrested for posing as a doctor so that his grant application to a Japanese foundation would be more convincing. He reportedly had some medical training that he drew upon in providing basic treatment for disaster survivors in underserved neighborhoods in the Ishinomaki area, and even the judge who presided over his trial was forced to concede that he was attempting to help evacuees, even if his behavior was reckless and callous (Japan Today 2012).

However, while NGOs overseas and inside of Japan did their best to respond, 3.11 exposed numerous systemic flaws in how we deal with international disasters in an increasingly globalized world. One initial lesson of 3.11 is that nongovernmental responses to massive disasters in other developed countries are likely to involve a larger and more diverse array of players than we are accustomed to seeing when there are humanitarian crises in the developing world. This is because developed countries tend to have more robust economic linkages and a richer set of grassroots ties to other developed countries. This makes it even more important to look outside of the “usual suspects” when thinking about what is happening with the overseas response.

Also, 3.11 drove home the point that international responses to disasters in developed countries are fundamentally about philanthropy, not the direct provision of humanitarian assistance. As many disaster experts noted in the immediate days after March 11, there is a highly limited role for “boots on the ground” in a country like Japan; rather, the most effective thing that NGOs can do to help is to channel resources to local responders. The centrality of philanthropy to international responses to disasters like 3.11 elevates the importance of the craft of international grantmaking and highlights the value of country expertise, capabilities that were underdeveloped at many of the US organizations responding to the disaster. For instance, one key element in grantmaking is an awareness of how to manage grantee expectations. In too many cases, already overstretched Japanese NGOs have felt that they were led on by US donors who inadvertently built up their hopes and monopolized valuable time by asking for a wide range of documentation before eventually turning down their funding requests. A greater knowledge of Japanese nonprofit culture and a deeper appreciation of the funder-grantee relationship could have saved considerable time and effort on both sides. Similarly, simplifying application processes—and, ideally, instituting a culturally appropriate unified application format for multiple overseas donors—could have gone far in lightening the burden on Japanese NGOs scrambling to meet needs in the disaster zone.

The disaster also highlighted the importance of cultivating cross-border relationships between humanitarian groups and philanthropic intermediaries before a disaster strikes. To some extent, the paucity of ties between American and Japanese NGOs in the field of humanitarian assistance can be seen as a particularly Japanese problem, given the relative underdevelopment of the country’s nonprofit sector. Still, it is easy to envision similar issues arising for US-based NGOs when dealing with Korea’s nongovernmental sector or with various European countries. This suggests that more effort needs to be put into building up international civil society linkages and nurturing habits of cooperation among overseas and domestic NGOs likely to be involved in disaster responses in developed countries. There is much that can be done to this end, including developing stronger ties between national coalitions of humanitarian assistance organizations; encouraging greater involvement by NGOs in Asia, the world’s most disaster-prone region, in forums for international humanitarian assistance and development organizations; and nurturing familiarity and habits of international cooperation by engaging NGOs from developed countries like Japan in small-scale joint initiatives with US-based groups in third countries.

Finally, 3.11 showed that coordination is even more challenging for disasters in developed countries. It seems natural for groups like InterAction, the umbrella organization for humanitarian assistance and development NGOs, to play a central role in disseminating information and facilitating donor coordination for overseas disasters in developed countries, just as they do for crises in developing countries. But given the likelihood that the response will be more of a grassroots phenomenon with a broader array of players, greater effort needs to be made to make more information and advice on the response easily accessible to NGO leaders outside of the field of humanitarian assistance. In particular, more needs to be done to connect humanitarian groups with the NGOs that have country expertise, especially those outside of the Washington DC “Beltway” where much of the public-private coordination involving humanitarian assistance organizations tends to take place. The same goes for philanthropic intermediaries that specialize in overseas giving. Bringing these circles closer together will not only enhance coordination but also allow each to benefit from the others’ unique insights and networks.

Similarly, if philanthropy is to be the core of the response, there are many steps that can be taken to share information on the recipient country’s nonprofit sector: the preparation of background papers on the national nonprofit system, the dissemination of basic guides to the country’s legal regulations, and the creation of databases that allow organizations to identify reputable local NGOs and see what they are doing in the disaster zone. These seemingly obvious resources were difficult to find in a timely manner in the case of Japan, despite efforts by various groups to provide them.17

Stronger coordination on the part of overseas donors can only go so far, though, without effective coordination within the country where the disaster strikes. This is a particular challenge for developed countries, which are unaccustomed to receiving outside assistance. In developing countries, donor roundtables that link international development NGOs, bilateral ODA agencies, UN agencies, and host governments can be repurposed to coordinate disaster aid but, as 3.11 showed, often there are no equivalent mechanisms in place in rich countries. In Japan, the staff of overseas organizations were invited to join discussions convened by Japan Platform and JANIC, but limited institutional capacity and linguistic and cultural barriers kept these forums from living up to their potential despite admirable efforts by the host organizations.18 Moreover, the domestic coordination mechanisms needed to bring together Japan’s professional humanitarian assistance NGOs and local-level groups were sorely lacking. This was exacerbated by the fact that the Japanese NGOs with the capacity and know-how to provide disaster relief on a large scale were internationally oriented ones that normally worked on disasters outside of Japan, and thus had few connections to local authorities and limited experience navigating the politics of rural Japan.

The experience of 3.11 suggests that there is much work to do in developed countries to build the capacity to receive assistance from overseas NGOs when a megadisaster occurs. This ranges from big picture issues to highly technical measures, such as encouraging organizations and coalitions that would be natural contact points for overseas donors to think through what is needed to take on the roles of being a neutral facilitator and a clearinghouse for information; exploring the feasibility of creating networks of volunteer translators that can assist in preparing documents for overseas organizations, particularly for countries like Japan, Korea, and others with uncommon languages; and analyzing whether domestic coordination networks are structured in such a way as to allow overseas organizations, and even domestic organizations that normally have an international orientation, to easily take part.

In a sense, the US nongovernmental response to 3.11 was a portent of what we are likely to see in the future when large-scale disasters strike other developed countries. The extraordinary response by American NGOs and the US public was surprising in its scope and complexity, and it suggests that the way we react to disasters abroad is being transformed by the advance of globalization, the revolution in communications technology, and changes in the nature of disaster philanthropy. Just as disasters are the sum of thousands of personal tragedies, the US response to 3.11 proved to be the amalgamation of millions of people-to-people ties to Japan. In our increasingly interconnected world, this grassroots reaction is likely to become one of the defining traits of overseas responses to megadisasters in developed countries and it needs to be taken into account when we grapple with one issue that we have barely begun to master—how to effectively assist developed countries suffering from massive humanitarian crises.

Endnotes

1. Data from a Japan Center for International Exchange (JCIE) survey of 1,170 American and Japanese nonprofit organizations and corporate donors covering the two years from March 2011 to March 2014 and reported in JCIE 2014.

2.Data from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)’s Financial Tracking Service website. The service depends on self-reporting by donors, which is less accurate for nongovernmental donors that for the governments that are members of the UN system, as indicated by the fact that more comprehensive surveys of US private giving by the University of Indiana’s Center on Philanthropy have found $1.45 billion in American private donations for Haiti, considerably more than the $1.27 billion that UN OCHA estimates for all private donors worldwide.

3.The data collected by OCHA, which normally is biased towards governmental funding, credits private giving with comprising 80 percent of total overseas aid for the 3.11 response. A better sense can be gained, however, by amalgamating data from several sources, including Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the analysis of that data for Japan’s annual almanac of philanthropy, Giving Japan 2012. Taken together, these suggest that nongovernmental sources provided roughly twice as much aid in monetary terms as governmental sources, highlighting how large of a role overseas private giving played in this disaster.

As background, the Japanese foreign ministry reports that there were 17.5 billion yen (US$184 million at US$1=95 yen) in cash donations by foreign governments, as well as a number of large in-kind donations. (The largest expenditures by foreign governments appear to be 40 billion yen (US$420 million) in oil donated by Kuwait, the $95 million that the US Congressional Research Service estimates was expended for Operation Tomodachi, and another 10,000 tons each of gasoline and diesel fuel at a market price of approximately US$25~30 million that was donated by China.) Combined, the largest cash and in-kind donations from foreign governments total 67 billion yen or roughly US$700 million, although these figures could be expected to increase by some 20 to 30 percent if the total costs of all in-kind goods and technical assistance could be quantified and included in the total.

In contrast, adding up the private giving from major donors surveyed by Giving Japan 2012 and JCIE’s survey of US donors—US$730 million (69.5 billion yen) from the United States, approximately US$188 million (17.9 billion yen) from Taiwan, US47 million (4.5 billion yen) from Korea, US$26 million (2.5 billion yen) from the United Kingdom), and US$252 million (24 billion yen) that was collected by Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies in other countries—indicates that roughly 118 billion yen, more than US$1.2 billion, originated with overseas private donors. As with government funds, these estimates could be expected to increase if more accurate counts were available.

For further information, see UN OCHA “Japan – Emergencies for 2011; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2012; Feickert and Chanlett-Avery 2011, 1; JCIE 2014; and Japan Fundraising Association 2012, 34-40.

4. An earlier version of this paper, which was published in Rebuilding Sustainable Communities after Disasters in China, Japan, and Beyond (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014), uses the estimate of $712.6 million in US giving. This came from 2013 Japan Center for International Exchange survey, and the estimate was later revised upwards to $730 million after more accurate and updated data could be collected in 2014.

5. Of the 120 organizations that collected more than $100,000, more than 40 had no prior experience working on disasters, and only one-third defined themselves primarily as humanitarian assistance organizations.

6. Two of the most prominent were essays on the Give Well blog (blog.givewell.org) and a widely circulated article by Reuters commentator Felix Salmon entitled “Don’t Donate Money to Japan” (March 14, 2011).

7. Taiwanese media reports indicate that 90 percent, or approximately US$235 million, of the total US$260.64 million collected in Taiwan came from private donors. (The Taipei Times 2013).

8. Author’s personal correspondence with Japan Society executive, March 15, 2013.

9. See, for instance, Network for Good 2006.

10 While there is an important place for cash grants-in-aid after a disaster, it is worth noting that there were many problems with these funds after 3.11. Intense public criticism arose about delays in distributing the funds but perhaps the most worrying phenomenon was the way that funds, which were disbursed as the slow pace of finalizing local rezoning plans was preventing people from investing in rebuilding homes and businesses, fed an extraordinary boom in bars and pachinko gambling parlors.

11. Donations for nonprofit activities include giving for religious organizations, educational organizations, and other similar organizations in the disaster zone that operate as nonprofit organizations. The Japanese Red Cross Society operates two major funds. Donations from within Japan and the general public overseas go into the first fund to be used for cash grants-in-aid for disaster victims, and donations from overseas Red Cross and Red Crescent societies and a few other overseas groups have been allocated to a second fund for relief and reconstruction efforts directly implemented by the Japanese Red Cross Society as well as a handful of nonprofit partners. Only donations to the second fund are counted as going for nonprofit activities.

12. Author’s estimates based on JCIE’s survey of US giving for Japan. While US donations are estimated to account for as much as one-quarter to one-third of all private pledges to Japanese nonprofits active in the disaster zone, one should keep in mind that they comprise a considerably smaller portion of overall income for these groups since private giving is just one of several streams of funding and government contracts and subsidies also cover a substantial portion of many organizations’ budgets.

13. Japanese embassy and consulate requests to avoid sending in-kind donations were initially reported by some media outlets as a Japanese refusal of all donations, but this was an obvious misunderstanding that arose out of faulty reporting. In fact, Japanese embassies quickly took the unprecedented of accepting cash donations themselves, receiving millions of dollars which they forwarded on to the Japanese Red Cross.

14. Author’s recollection from the July 21, 2011 “Funding Conference on US-Japan Cooperation on Supporting the Japan Disaster Response” that convened representatives from more than 40 American and Japanese NGOs, foundations, and corporations in New York to share information on challenges they were facing in their disaster responses. This was sponsored by JCIE, the Japan Foundation Center for Global Partnership, and the Institute of International Education.

15. Author’s interview with a representative of a US donor organization, March 14, 2013.

16. In contrast, there were numerous embarrassing nonprofit scandals in the United States after the 9/11 attacks and the Hurricane Katrina response. (See, for example, “9/11 Charities Under Scrutiny for Failing to Raise Money for Victims,” The Associated Press, August 25, 2011, or Adam Nossiter, “Katrina: US Raids New Orleans Agency in Scandal Over Housing Cleanup Program,” The New York Times, August 11, 2008.) Likewise, there has been considerable press coverage of the misuse of funds after the Sichuan Earthquake by Chinese organizations and following the Haiti Earthquake by groups such as Wyclef Jean’s Yele Haiti. (See Edward Wong, “An Online Scandal Underscores Chinese Distrust of State Charities,” The New York Times, July 3, 2011, and Deborah Sontag, “In Haiti, Little Can be Found of a Hip-Hop Artist’s Charity,” The New York Times, October 11, 2012.)

In comparison, surprisingly few scandals have come to light in connection with the 3.11 response. On the US side, in the first few weeks after 3.11, fraudsters were reported to have put up fake fundraising websites, most often claiming to be collecting funds for the Japanese Red Cross Society, but these were quickly discredited. Meanwhile, in Japan, there have been rumors in nonprofit circles of a few isolated incidents of accounting misconduct by NGOs in the disaster zone, for example, involving the submission of the same receipts to two different donors in order to double-bill certain direct expenses, however this should be understood in the proper context. It appears that much of this double-billing is so that NGOs can cover other expenses necessary to carry out the programs they committed to implement, such as staff salaries and overhead, because many funders from Japan and elsewhere insist on paying only select direct expenses and ridiculously small amounts for salaries, plus there are few alternative funding sources for general operational support. So, while these NGOs are not abiding with the letter of the law, so to speak, what they are doing can be said to be in keeping with the overall spirit in which they were given funds.

17. For example, JCIE worked to create a public, online database (www.jcie.org/311database) that would allow overseas donors to identify potential grantees working in the geographic and issue areas where they were focusing their funding and enable Japanese NGOs to identify which overseas organizations were providing funds. However, technical problems with the software design and limited staff capacity prevented the database from being launched until almost two years after the disaster.

18. Within Japan, even the members of Japan Platform and JANIC had considerable difficulty in coordinating with government and local authorities. One illustrative example involved their main channel for consultations with the national government. They were accustomed to responding to overseas disasters, and had developed a strong working relationship with the Japanese foreign ministry, which regularly organizes government-NGO consultative sessions. However, because this was a domestic disaster, a different agency, the Cabinet Office, was mandated to take the lead and it had much less appreciation of the role of NGOs in the response, plus there were no preexisting coordination mechanisms that could be activated for it to engage with NGOs.